Recipes

- G.E.N

- May 20, 2025

- 15 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2025

In a bid to get better at cooking, I'm picking a new food each month and trying to perfect it. Here are my favourite recipes so far, along with some context (to help it stick in your brain).

Healthy Snack

200g Oats

2 Bananas

70g Chopped Walnuts

70g Chopped Dates

70g Dark Chocolate Chunks

1 tbsp Honey

1 tbsp Rapeseed Oil

2 tsps Ground Cinnamon

2 Eggs (beaten)

50ml Milk

Heat your (fan) oven to 170C and cover a 20cm square baking tray (or something with a similar volume) with baking paper.

Add the oats, dates, walnuts, small chocolate chunks and cinnamon to a large bowl, before throwing in a pinch of salt.

In a separate bowl mash the bananas together then add the honey, eggs, oil and milk, and give them a good stir.

Add the wet ingredients to the dry and give it a good mix before adding into into your baking tray. Firmly compress the mixture down with the back of a spoon until it's all the same height (about an inch).

Cook it for around 30 minutes, then carefully take it out of the tin and let it cool on a wire rack for 20 minutes. Then cut them up into small squares to have throughout the week.

Context

You can eat these pretty much guilt free, as they're sweet but all the ingredients have beneficial properties: oats and bananas are obviously very good for you, walnuts are often cited as the healthiest nut, cinnamon is one of the most beneficial spices, dates are sugary but also full of nutrients and fibre, nice dark choc (like Green and Black's 85%) improves blood flow and lowers blood pressure, eggs are full of beneficial proteins, rapeseed oil is one of the healthier cooking oils and high in unsaturated fats, and honey is rich in antioxidants that help to protect your immune system. Job's a good'un.

My Cookies

(Makes seven cookies)

200g Strong Bread Flour

1 tsp Cornflour

10g Cocoa Powder

1/2 tsp Baking Powder

1/2 tsp Baking Soda

1/4 tsp Salt

115g Unsalted Butter (softened to room temp)

95g Light Brown Sugar

45g Caster Sugar

1 Egg (room temperature)

1/2 tsp Vanilla Extract

100g Dark Chocolate (chips or small chunks)

70g Milk Chocolate (chips or small chunks)

Heat your (fan) oven to 160C and cover a large baking tray with baking paper.

Add your flours, the cocoa powder, the baking powder, baking soda and salt into a bowl. Give it a good stir with a whisk.

Add the butter and sugars to a separate bowl and cream it. (You can either use a hand mixer for this or a stand mixer with the beater adapter fitted - it takes about 3 minutes to cream it properly, stopping now and again to scrape down the bowl.)

Add the egg and vanilla extract to the creamed sugar, before giving it another quick mix (just to combine the ingredients).

Add your bowl of flour into the wet ingredients and give it another short mix, so the dough begins to come together. Now fold in the chocolate chunks by hand.

Weigh out 100g of the dough and very roughly shape it into a ball, before placing it onto the baking tray. Repeat for the other six cookies.

Cook for about 15 minutes, then allow the cookies to rest on the hot baking tray for five minutes before transferring to a wire rack.

Context

I’ve made lots of cookies this month: from Nigella recipes, to BBC Good Food suggestions, to various takes on the Levain method (which is a bakery in New York famous for producing oversize, thick and chewy cookies). However, after learning the basic methods I then tried to create my own perfect cookie from scratch, based on my own taste.

I’ve used bread flour because the extra gluten adds chewiness to the cookie, while the cornflour helps to keep the texture delicate. However, you could easily swap these out and just use plain flour instead (you don’t even have to add the cocoa powder).

The basic rule of thumb seems to be that baking powder helps the cookie to rise, while baking soda helps it to spread out and flatten during the baking process. Cookie recipes are fairly forgiving, so you can change up most of the ingredients in this recipe for alternatives, but don't forget to keep some form of brown sugar in there as you need the acidity for the baking soda to work (the extra molasses of brown sugar also helps to keep the cookie moist).

While these cookies keep pretty well for a few days, it's much better to just freeze the balls of uncooked dough if you're not going to eat them straight away - that way you can just pop them in the oven whenever you fancy a freshly baked cookie. To cook the dough from frozen, keep the oven at 160C but cook them for about 20 minutes. Cookies are actually even tastier when cooked from frozen, as they will have had more time for the flavours to develop, and the centre will remain particularly moist as they won’t spread out as much during the cooking process.

Blueberry Muffins

(Makes about six)

100g caster sugar

60g of softened (not melted) unsalted butter

1 egg

1/2 tsp vanilla extract

135g plain flour

1/4 tsp salt

1 tsp baking powder

Pinch of ground cinnamon

60ml whole milk

pack of blueberries

2 tsps of demerara sugar

Heat your fan oven to 170 C and line a muffin tray with six muffin cases.

Cream the caster sugar and butter in a mixer (start it off slow then take it to a middle speed for about 3 minutes - it will go pale and fluff up a bit). Then add one egg at a time and briefly mix these in as well, before stirring in the vanilla extract.

In a separate bowl, add all the dry ingredients together - the flour, salt, baking powder and cinnamon - and give it a good stir. Then start adding this into your wet mix, along with the whole milk, stirring just enough so it's all incorporated.

Squish a quarter of your blueberries and stir them into your wet mixture, then toss the rest of the blueberries in a little flour and fold them into the mixture as well.

Spoon the mixture into your muffin cases and finish them with a little demerara sugar on top*. Bake for 30 minutes.

Scones (sweet and cheese)

(Makes about six)

For sweet scones you need:

250g self-raising flour

60g butter

Pinch of salt

1 tsp baking powder

Handful of sultanas

90ml milk

40g sugar

1/2 a beaten egg

1/4 tsp vanilla extract

For cheese scones you need:

225g self-raising flour

50g butter

1 tsp baking powder

100g of grated hard cheese like mature cheddar (or cheddar and parmesan/comté)

150ml milk

Heat your fan oven to 200 degrees.

Cut the cold butter into chunks and put into a bowl with the flour, salt, and baking powder. Then, using your fingers, rub the flour and butter together until all the flour is coated in the fat and the mixture almost looks like breadcrumbs.

If making sweet scones add the sultanas to the bowl, if making cheese scones add the the grated cheese (keeping a bit back to put on top of the scones later on).

For sweet scones, now add the milk, sugar, egg and vanilla extract into a jug and give it a good stir, before adding 95% of this mixture into the bowl. If making cheese scones, just add the milk straight into the bowl (but you might not need all of it).

Flour a surface, then bring the mixture together in the bowl before very briefly kneading it a couple of times on the floured surface - you're looking for a mixture that is a unified mass but isn't too wet or sticky. Then pat this dough out so it's an inch thick.

Using a 5-7cm cutter, cut your scones out and place them on a tray lined with baking paper. (It's best to add a bit of flour to the cutter first, and go straight in and out without twisting the cutter around.) Then for the sweet scones, brush the tops with some of the sugary milk mixture you kept back, while for the cheese scones brush the tops with some milk then add the remaining grated cheese*. Bake in the oven for 10-15 minutes.

American Style Buttermilk Pancakes

(Makes 6-8)

125g plain flour

15g sugar (caster or granulated)

Pinch salt

3/4 tsp baking powder

1/4 tsp baking soda

240ml buttermilk*

30g melted butter

1/2 tsp vanilla extract

1 egg

Put all your dry ingredients into a bowl and stir (that's the flour, sugar, salt, baking powder and baking soda).

In a separate jug add your buttermilk, melted butter, vanilla extract and egg. Whisk these together until combined.

Add the wet ingredients into the dry ingredients and whisk them together until most of the lumps have gone. (Don't go overboard with this, just roughly.) Don't stir this mixture again, not at any point.

Turn your oven to 100 degrees, then heat a bit of butter/rapeseed oil/both in a hot frying pan. Place a dollop of the batter into the pan and form it into a rough circle before letting it cook. Don't touch it. Wait until you see bubbles and holes appearing on top of your pancake, then flip it over with a plastic spatula and give it a minute or two on the other side (don't be tempted to press down on it). Take it out and keep it warm in the oven while you make the rest of your pancakes.

Context

You use demerara sugar on top of the muffins, not caster sugar, because the demerara has larger and coarser crystals which are less likely to burn and melt.

You don't egg/milk wash the sides of the scones as this can stop them rising.

If you don't have buttermilk you can simply add a little lemon or vinegar (like apple cider vinegar) to regular whole milk then let it stand for a few minutes. This will give it the acidic tang you need, and help it to react with the baking soda.

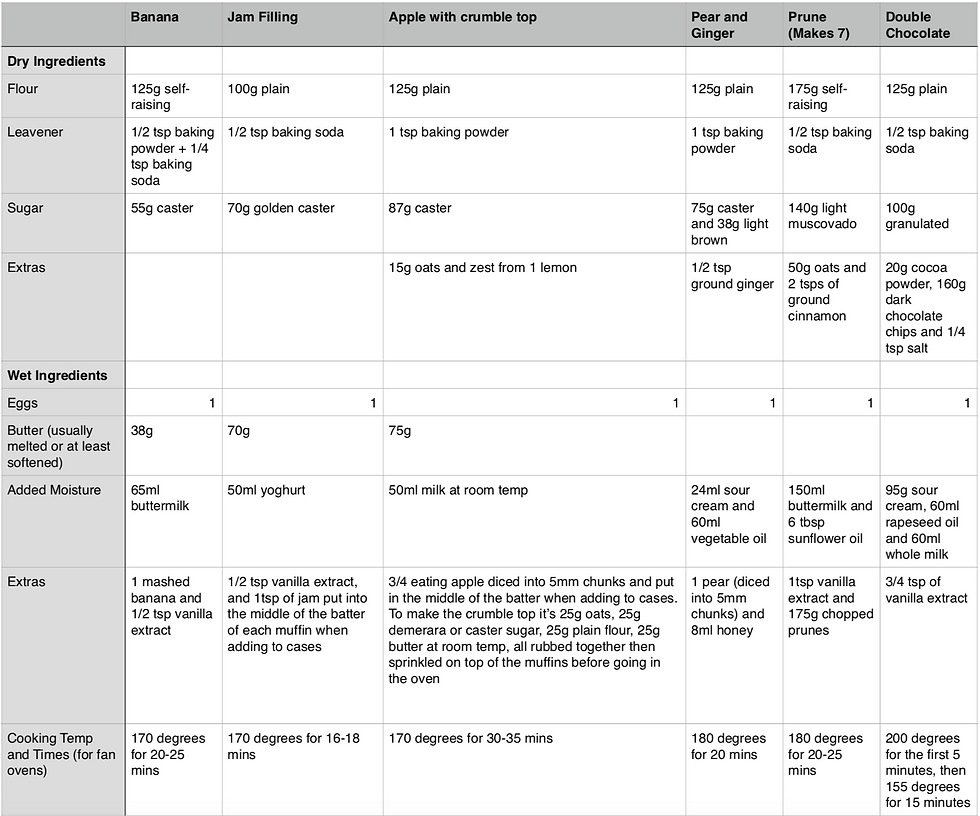

While the above blueberry muffin recipe includes a creaming stage, most recipes are even more straightforward; it's simply a case of adding all your wet ingredients into one bowl, all your dry ingredients into another, then combining them with minimal stirring and chucking them in the oven - really, really easy. Below is a look-up table for other muffin flavours I tried and enjoyed, and as you can see they're all roughly the same recipe with variations on a theme (some use oil instead of butter, or different kinds of sugar etc). I particularly recommend the pear and ginger ones.

If you're going to use one type of oil in baking, rapeseed oil seems to be a good shout as it's one of the slightly healthier options and has a neutral flavour.

Egg custard tarts with sweet shortcrust pastry

This recipe makes six tarts, which is plenty, you fat pig.

For the pastry

120g plain flour

60g unsalted butter (must be cold)

30g icing sugar

1 egg yolk

For the custard

120ml whole milk

100ml double cream

1/2 teaspoon of ground cinnamon

2 eggs

30g caster sugar

1/2 nutmeg

Cut the butter into chunks then chuck it into a food processor along with the plain flour. Blitz it for ten seconds until it looks like breadcrumbs, then add the icing sugar, egg yolk, and 2 tablespoons of cold water. Keep pulsing it, on and off, until this mixture comes together into a dough (should only take half-a-dozen pushes - if it’s not coming together add just a little more water). Gently work the pastry into a ball on a lightly floured surface, then cover it in cling film and whack it in the fridge for an hour.

After it’s done cooling, grease the bottom of a muffin tray then roll out your dough so it’s the thickness of a £1 coin. Using a cutter, or large mug, cut circles out of the dough then gently place these into the muffin tray compartments, making sure the dough comes to the top and there are no big air bubbles underneath (just lightly squidge them down with your thumbs). Prick the base of the tarts with a fork then put the tray back in the fridge for 30 minutes.

Heat your fan oven to 180 degrees, then cover each individual pastry tart with baking paper, making sure you cover the pastry completely, then fill them with ceramic baking beans or rice. Cook them in the oven for 12-15 minutes, then take them out, remove the baking beans and baking paper, and give them another 5 minutes in the oven to brown the bottoms. (This process, of cooking the pastry before the filling is added, is called ‘blind baking.’)

Meanwhile, add your whole milk, double cream and cinnamon into a saucepan and gently heat it on the hob, continuing to stir from time to time.

Put your caster sugar in a heatproof bowl, then add 1 whole egg and 1 egg yolk. Give these a moderate whisk and bring them all together.

When the milk has reached 80 degrees, you’re going to add it to the eggs and sugar in the bowl. This is called ‘tempering’ and the key is to add the hot milk very slowly at first, whisking all the time: you don’t want to shock the eggs into scrambling by raising the temperature too quickly, so you’re trying to gently get them there. Continue pouring until all of the milk has been added, stirring the whole time, then strain this mixture into a pourable jug.

Turn the oven down to 140 degrees then pour the custard into each of the individual tarts, taking the level right to the rim of the pastry. Grate a good dusting of nutmeg onto the top of each tart, then put them in the oven for 10-15 minutes.

Now, experienced bakers will be able to judge when the custard is ready by eye, and they suggest taking the tarts out when ‘there’s still a bit of wobble on the custard but not too much.’ Obviously that’s mental advice, so I prefer to use a thermometer, and you want the custard to reach a temperature between 75-79 degrees (if it goes over 83 degrees the eggs will start to scramble). When they hit that temp, turn the oven off and open the oven door but leave the tray in there for 5 minutes, as you don’t want them to go from hot to cold too quickly. Then bring the tarts out, allow them to cool completely in their tray for about an hour, and tuck in.

Context

Pastry: Most pastries are made from a relatively low protein flour (like plain flour), a fat (like butter or lard), and a little liquid (such as egg or water). Sweet shortcrust pastry includes sugar as well, obviously.

When making a regular bread dough, you want to use quite a bit of water to fuse the particles of wheat together and encourage gluten development, but with shortcrust pastry we don't want this gluten development. The pastry is called 'short' because we want to keep the gluten strands short, instead of long and elastic - this is what creates that crumbly, melt-in-your-mouth texture, rather than a chewy, doughy one. So we aim to use as little water as possible throughout the process - and it's also why we begin by rubbing the fat into the flour (or blitzing it in a food processor), so we can effectively waterproof the grains and prevent too much gluten development.

Fats, like butter and lard, are a collection of molecules in both solid crystal and liquid form. Above 25% solids, and the fat is too hard and brittle to roll into an even layer of pastry, below 15% and it’s too soft to work, meaning the dough won’t hold its shape and will leak liquid. Butter has the right consistently to make pastry when it’s between 15-20 degrees (lard is useable up to 25 degrees). This is why you have to make sure the butter is cold before you start, that you don’t overwork it with warm hands, and you have to keep chilling the dough at various stages, so it doesn't become too hot, leak moisture and shrink during cooking.

Eggs: Both the white and yolk of an egg are essentially bags of water containing dispersed protein molecules. When you heat an egg, the proteins unfold, tangle with each other, and bond to form a network. While there's still much more water than protein, this new protein network traps the water, meaning it can’t flow anymore, and so the egg becomes a moist solid. However, if you heat the egg too much, you cause the proteins to bond exclusively to each other and force the water out of the network completely, which is what happens when you get rubbery eggs, or your scrambled eggs split into water and eggy lumps. So the key to cooking all egg dishes, including custards, is to heat them to the point the proteins come together but not much more.

Adding milk or cream to the egg disperses the protein molecules even further, but they will still be able to set a liquid into a solid gel, or custard, at the correct ratio. The key ratio to remember is that 1 whole egg will set 250ml of liquid.

There’s actually quite a lot of leeway with custards, and you can use any combination of milk, cream or alternative liquids as long as you stay within the 250ml ratio. Also, you can add a lot more than one egg to that 250ml. Going on the basis that one egg white, or one egg yolk, equals half an egg, you can add any combination of these to create any texture you like, remembering that egg whites will create a stiffer custard, while egg yolks will make it creamier. So if you add 2 whole eggs to 250ml, you’ll have something akin to a crème caramel, while adding 4 egg yolks to 250ml will create a crème brûlée texture. For his award-winning custard tart, Marcus Wareing uses 9 yolks for 500ml of whipping cream. Seems a bit much.

FYI, the best books I've read for this sort of context are Lateral Cooking and On Food And Cooking.

Spelt Soda Bread

Ingredients (makes a small loaf)

200g Wholemeal spelt flour

150g Plain flour

25g Rolled oats

300ml Buttermilk

3/4 tsp Bicarbonate of soda

1/2 tsp Salt

Method

Preheat the oven to 200 degrees (220 if you don't have a fan oven) then stick a baking sheet on a tray.

Grab a large bowl and add all the dried ingredients: both the flours, the oats, the bicarbonate of soda and the salt. Give it a good stir and make a well in the middle.

Add the buttermilk while gently stirring with a fork to bring it all together. You're looking to hit that sweet-spot where the dough is soft and mouldable but not too wet and sticky - annoyingly the consistency of buttermilk is slightly different at each supermarket (Tesco's buttermilk is more like milk while the Sainsbury's one is thicker like yoghurt), so you might need slightly less than 300ml or slightly more. But don't panic, you can't go too wrong with 300ml, and you can always add a dash of regular milk if you don't have enough buttermilk left.

On a floured surface, gently form it into a ball, but don’t knead it and don’t be too rough with it. Place it on the baking sheet and flatten the top down so it's a low dome shape, about 4 cm deep (it isn't going to rise a huge amount during baking so don't make it too thin). Dust the top of the dough with a little extra flour.

Grab a sharp knife and score a large cross along the top, going quite deep with this cut (about 1/2 way through the dough) then prick each corner once to 'let the fairies out'. Put it in the oven.

Cook for 25-30 minutes (every oven is a bit different). To check it’s done turn it over and tap the bottom, which should sound hollow. You can also prod it with a skewer and check the skewer comes out clean, or use a food thermometer and check it's above 92 degrees. Leave it to cool on a wire rack for 30 minutes then tuck in. I often just top mine with butter, but it goes especially well with smoked salmon and soups. You can toast any leftovers the next day.

Context

While most breads rely on yeast to rise, soda bread relies on the bicarbonate of soda.

Yeast and bicarbonate of soda both produce carbon dioxide gas, which essentially gets trapped in the glutinous flour dough, causing it to stretch and expand. The yeast needs time to produce this gas, which is why you let it prove, whereas the bicarb begins producing the CO2 as soon as it comes into contact with an acidic liquid. However, it will never reach the heights of a bread made with yeast so expect a more dense, crumbly bread.

As mentioned, the bicarbonate of soda begins working when it comes into contact with any acidic liquid, which in this recipe is the buttermilk. Most people suggest getting the dough into the oven nice and quickly after you’ve mixed all the ingredients together, so the carbon dioxide isn’t allowed to escape into the atmosphere - which is also why you don’t knead the bread and should be fairly gentle with it. You knead bread to improve the gluten formation - gluten is the protein in wheat - but soda bread doesn’t require extensive gluten development for its structure, and kneading it will only release the CO2 and cause the dough to become tough and chewy.

What’s the difference between bicarbonate of soda, baking soda, and baking powder? Turns out bicarbonate of soda and baking soda are the same thing, and then baking powder is bicarbonate of soda with acidic ingredients already mixed in, so all you have to do is add liquid or heat to begin the reaction. They can’t quite be used interchangeably though, so do use the right one.

The reason I’ve suggested wholemeal spelt flour, instead of just wholemeal flour (which will actually rise better than spelt), is that 'ancient grains' like spelt and rye are more easily digested than regular wholemeal, so this already fibrous recipe should be easier on your belly. Feel free to swap in regular wholemeal flour instead, but best not to use strong bread flour - strong flour is for recipes requiring a strong gluten network, as it has a higher protein/gluten content than regular flour, and as previously mentioned you don’t want or need that for soda bread.

Why have I used some plain flour instead of making it all wholemeal? Because wholemeal flour on its own can make soda breads too dense - wholemeal flour is made from the entire wheat grain, so contains bran and germ, which act like tiny razor blades that shred the gluten strands making the dough less elastic, harder to work and means that it won't rise as well. The plain flour is there to counteract all this.

If you're looking to add one more ingredient for a simple twist, throw a big handful of mixed fruit into the mixing bowl (those bags of raisins and sultanas etc that you get). The sweetness helps mellow the wholemeal taste, and some Irish people might now call this more of a wheaten bread, instead of a brown soda bread, but I refuse to get dragged into this bread sectarianism.